Thursday, September 22, 2011

Saturday, September 3, 2011

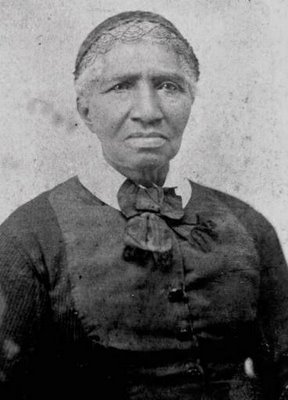

Black Women Of The Old West - From Book Black People by Dr. Leroy Vaughn

Women’s rights advocate and Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman would be proud of the role modern Black women are playing in the world’s revitalization. Michelle Obama and others are living the strength and wisdom that comes from the journey of earned power.Traditional history mentions the explosive accomplishments and contributions of Mary McCloud Bethune, Rosa Parks, Rep. Shirley Chisholm, Rev. Della Reese Lett and Madam C. J. Walker. There are many more souls in this rich tapestry.

Dr. Leroy Vaughn, MD, MBA, Historian has a great chapter in his book BLACK PEOPLE AND THEIR PLACE IN WORLD HISTORY called “Black Women Of The Old West”, where he introduces Biddy Bridget Mason (1815-1891), Clara Brown (1806-1888) and Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814-1903).

Here’s the information on these women from Dr. Vaughn’s book, BLACK PEOPLE AND THEIR PLACE IN WORLD HISTORY pages 114-117.

“Although our novels and movies are filled with heroes from the old west, African American heroes are virtually never mentioned. Moreover, historians have also contributed to this unjust and unbalanced recording of our glorious western saga by completely ignoring the many accomplishments of Black men and women, despite the fact they were accurately reported in newspapers, government records, military reports, and pioneer memoirs. As members of a double minority, Black women have suffered an even greater historical injustice, although they were an integral part of the western fabric. Nothing more clearly demonstrates the contributions of Black women to the western tradition than the biographies of Biddy Bridget Mason, Clara Brown, and Mary Ellen Pleasant.

Biddy Bridget Mason (1815-1891) was born into slavery and given as a wedding gift to a Mormon couple in Mississippi named Robert and Rebecca Smith. In 1847 at age 32, Biddy Mason was forced to walk from Mississippi to Utah tending cattle behind her master’s 300-wagon caravan. After four years in Salt Lake City, Smith took the group to a new Mormon settlement in San Bernardino, California in search of gold. When Biddy Mason discovered that the California State Constitution made slavery illegal, she had Robert Smith brought into court on a writ of habeas corpus, and the court freed all of Smith’s slaves. Now free, Mason and her three daughters (probably fathered by Smith) moved to Los Angeles where they worked and saved enough money to buy a house at 331 Spring Street in downtown Los Angeles.

Knowing what it meant to be oppressed and friendless, Biddy Mason immediately began a philanthropic career by opening her home to the poor, hungry, and homeless. Through hard work, saving, and investing carefully, she was able to purchase large amounts of real estate including a commercial building, which provided her with enough income to help build schools, hospitals, and churches. Her most noted accomplishment was the founding of First African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, now the oldest church in Los Angeles, where she also operated a nursery and food pantry. Moreover, her generosity and compassion included personally bringing home cooked meals to men in state prison. In 1988, Mayor Tom Bradley had a tombstone erected at her unmarked gravesite and November 16, 1989 was declared “Biddy Mason Day”. In addition, the highlights of her life were displayed on a wall of the Spring Center in downtown Los Angeles, an honor befitting Los Angeles’s first Black female property owner and philanthropist.

Clara Brown (1806-1888) is another who dedicated her life to the betterment of others. She was born as a slave in Virginia and then sold at age three to the Brown family in Logan, Kentucky. At age 35, her master died, and her slave husband, son, and daughter were sold at auction to different owners. After 20 additional years in slavery, she was able to buy her freedom and immediately headed west to St. Louis. At age 55, she agreed to serve as cook and laundress in exchange for free transportation in a caravan headed for the gold mines of Colorado. Clara Brown established a laundry in Central City and as her resources expanded, she opened up her home, which served as a hospital, church, and hotel to the town’s less fortunate.

Under her direction, the first Sunday school developed, and moreover, the whole town turned to her during illness because she was such a good nurse. Frequently, she even “grubstaked miners who had no other means of support while they looked for gold in the mountains and was repaid handsomely for her kindness and generosity by those who struck pay dirt.” Far and wide, she was known as “Aunt Clara” and as “the Angel of the Rockies”.

By the end of the Civil War, Clara Brown had accumulated several Colorado properties and over $10,000 in cash. Since slavery was over, she used her fortune to search for relatives in Virginia and Kentucky and returned with 34 of them including her daughter. She continued her philanthropy among the needy for the rest of her life and also spent large sums of money helping other Blacks come west. Upon her death at age 82, the Colorado Pioneers Association buried her with honors, and a plaque was placed in the St. James Methodist Church stating that her house was the first home of the church.

Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814-1903), a former slave, moved to San Francisco in 1849 where she opened a successful boarding house, famous for cards, liquor, and beautiful women. She was also a partner of Thomas Bell, cofounder of the first “Bank of California.” As a businesswoman, she was called mercurial, cunning, cynical, and calculating, but personally she was softhearted and had a passion for helping the less fortunate who called her “the Angel of the West”. She was a leader in California for the protection of abused women and children and helped build and support numerous “safe havens” for them. Mary Ellen Pleasant hated slavery and frequently rode into the rural sections of California to rescue people held in bondage. Because of Pleasant, the entire Black community of San Francisco received a warning from one judge for “the insolent, defiant, and dangerous way that they interfered with those who were arresting slaves.” Mary Ellen Pleasant used most of her fortune to aid fugitive slaves. “She fed them, found occupations for them, and financially backed them in numerous small businesses.” In 1858, she gave $30,000 to John Brown to help finance his raid at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. This White abolitionist had hoped to capture the national armory and distribute the weapons to slaves for a massive insurrection. During the Civil War, Pleasant raised money for the Union cause and continued to fight for civil rights. Her tombstone epitaph read: “Mother of Civil Rights in California” and “Friend of John Brown”.

Brief biographies of Biddy Bridget Mason, Clara Brown, and Mary Ellen Pleasant serve to illustrate the enormous contributions and accomplishments of Black women in the old west. Era Bell Thompson in “American Daughter” clearly states the problem: “Black women were an integral part of the western and American tradition. It both impairs their sense of identity and unbalances the historical record to continue to overlook the role of Black women in the development of the American west.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BLACK WOMEN OF THE OLD WEST

Billington, M & Hardaway, E. (eds.) (1998) African Americans on the Western Frontier. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Bruyn, K. (1970) Aunt Clara Brown: Story of a Black Pioneer - Boulder, CO: Pruett Publishing Co.

James, E. & James J. (eds.) (1971) Notable American Women. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Katz, W. (1992) Black People Who Made the Old West, Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Lerner, G. (1979) The Majority Finds Its Past: Placing Women in History. New York: Oxford University Press.

Myres, S. (1982) Westering Women: The Frontier Experience. 1880-1915. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Pelz, R. (1989) Black Heroes of the Wild West. Seattle: Open Hand Publishers.

Ravage, J. (1977) Black Pioneers: Images of the Black Experience on the North American Frontier. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press.

Riley, G. (1981) Frontierswomen: The Iowa Experience. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

Savage, W. (1976) Blacks in the West. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Sterling, D. (1984) We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Thompson, E. (1986) American Daughter. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society.

I rewrote Langston Hughes’s piece HARLEM.

What happens to a dream achieved?

It doesn’t dry up like a raisin in the sun.

It doesn’t fester like a sore and then run.

It don’t stink like rotten meat.

It don’t crust and sugar over like a syrupy sweet.

It don’t sag like a heavy load.

It just explodes!!!

We seem to be turning in the direction of an explosion of blessings built on the victories and sacrifices of the past.

Dr. Leroy Vaughn, MD, MBA, Historian has a great chapter in his book BLACK PEOPLE AND THEIR PLACE IN WORLD HISTORY called “Black Women Of The Old West”, where he introduces Biddy Bridget Mason (1815-1891), Clara Brown (1806-1888) and Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814-1903).

Here’s the information on these women from Dr. Vaughn’s book, BLACK PEOPLE AND THEIR PLACE IN WORLD HISTORY pages 114-117.

“Although our novels and movies are filled with heroes from the old west, African American heroes are virtually never mentioned. Moreover, historians have also contributed to this unjust and unbalanced recording of our glorious western saga by completely ignoring the many accomplishments of Black men and women, despite the fact they were accurately reported in newspapers, government records, military reports, and pioneer memoirs. As members of a double minority, Black women have suffered an even greater historical injustice, although they were an integral part of the western fabric. Nothing more clearly demonstrates the contributions of Black women to the western tradition than the biographies of Biddy Bridget Mason, Clara Brown, and Mary Ellen Pleasant.

Biddy Bridget Mason (1815-1891) was born into slavery and given as a wedding gift to a Mormon couple in Mississippi named Robert and Rebecca Smith. In 1847 at age 32, Biddy Mason was forced to walk from Mississippi to Utah tending cattle behind her master’s 300-wagon caravan. After four years in Salt Lake City, Smith took the group to a new Mormon settlement in San Bernardino, California in search of gold. When Biddy Mason discovered that the California State Constitution made slavery illegal, she had Robert Smith brought into court on a writ of habeas corpus, and the court freed all of Smith’s slaves. Now free, Mason and her three daughters (probably fathered by Smith) moved to Los Angeles where they worked and saved enough money to buy a house at 331 Spring Street in downtown Los Angeles.

Knowing what it meant to be oppressed and friendless, Biddy Mason immediately began a philanthropic career by opening her home to the poor, hungry, and homeless. Through hard work, saving, and investing carefully, she was able to purchase large amounts of real estate including a commercial building, which provided her with enough income to help build schools, hospitals, and churches. Her most noted accomplishment was the founding of First African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, now the oldest church in Los Angeles, where she also operated a nursery and food pantry. Moreover, her generosity and compassion included personally bringing home cooked meals to men in state prison. In 1988, Mayor Tom Bradley had a tombstone erected at her unmarked gravesite and November 16, 1989 was declared “Biddy Mason Day”. In addition, the highlights of her life were displayed on a wall of the Spring Center in downtown Los Angeles, an honor befitting Los Angeles’s first Black female property owner and philanthropist.

Clara Brown (1806-1888) is another who dedicated her life to the betterment of others. She was born as a slave in Virginia and then sold at age three to the Brown family in Logan, Kentucky. At age 35, her master died, and her slave husband, son, and daughter were sold at auction to different owners. After 20 additional years in slavery, she was able to buy her freedom and immediately headed west to St. Louis. At age 55, she agreed to serve as cook and laundress in exchange for free transportation in a caravan headed for the gold mines of Colorado. Clara Brown established a laundry in Central City and as her resources expanded, she opened up her home, which served as a hospital, church, and hotel to the town’s less fortunate.

Under her direction, the first Sunday school developed, and moreover, the whole town turned to her during illness because she was such a good nurse. Frequently, she even “grubstaked miners who had no other means of support while they looked for gold in the mountains and was repaid handsomely for her kindness and generosity by those who struck pay dirt.” Far and wide, she was known as “Aunt Clara” and as “the Angel of the Rockies”.

By the end of the Civil War, Clara Brown had accumulated several Colorado properties and over $10,000 in cash. Since slavery was over, she used her fortune to search for relatives in Virginia and Kentucky and returned with 34 of them including her daughter. She continued her philanthropy among the needy for the rest of her life and also spent large sums of money helping other Blacks come west. Upon her death at age 82, the Colorado Pioneers Association buried her with honors, and a plaque was placed in the St. James Methodist Church stating that her house was the first home of the church.

Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814-1903), a former slave, moved to San Francisco in 1849 where she opened a successful boarding house, famous for cards, liquor, and beautiful women. She was also a partner of Thomas Bell, cofounder of the first “Bank of California.” As a businesswoman, she was called mercurial, cunning, cynical, and calculating, but personally she was softhearted and had a passion for helping the less fortunate who called her “the Angel of the West”. She was a leader in California for the protection of abused women and children and helped build and support numerous “safe havens” for them. Mary Ellen Pleasant hated slavery and frequently rode into the rural sections of California to rescue people held in bondage. Because of Pleasant, the entire Black community of San Francisco received a warning from one judge for “the insolent, defiant, and dangerous way that they interfered with those who were arresting slaves.” Mary Ellen Pleasant used most of her fortune to aid fugitive slaves. “She fed them, found occupations for them, and financially backed them in numerous small businesses.” In 1858, she gave $30,000 to John Brown to help finance his raid at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. This White abolitionist had hoped to capture the national armory and distribute the weapons to slaves for a massive insurrection. During the Civil War, Pleasant raised money for the Union cause and continued to fight for civil rights. Her tombstone epitaph read: “Mother of Civil Rights in California” and “Friend of John Brown”.

Brief biographies of Biddy Bridget Mason, Clara Brown, and Mary Ellen Pleasant serve to illustrate the enormous contributions and accomplishments of Black women in the old west. Era Bell Thompson in “American Daughter” clearly states the problem: “Black women were an integral part of the western and American tradition. It both impairs their sense of identity and unbalances the historical record to continue to overlook the role of Black women in the development of the American west.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BLACK WOMEN OF THE OLD WEST

Billington, M & Hardaway, E. (eds.) (1998) African Americans on the Western Frontier. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Bruyn, K. (1970) Aunt Clara Brown: Story of a Black Pioneer - Boulder, CO: Pruett Publishing Co.

James, E. & James J. (eds.) (1971) Notable American Women. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Katz, W. (1992) Black People Who Made the Old West, Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Lerner, G. (1979) The Majority Finds Its Past: Placing Women in History. New York: Oxford University Press.

Myres, S. (1982) Westering Women: The Frontier Experience. 1880-1915. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Pelz, R. (1989) Black Heroes of the Wild West. Seattle: Open Hand Publishers.

Ravage, J. (1977) Black Pioneers: Images of the Black Experience on the North American Frontier. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press.

Riley, G. (1981) Frontierswomen: The Iowa Experience. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

Savage, W. (1976) Blacks in the West. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Sterling, D. (1984) We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Thompson, E. (1986) American Daughter. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society.

I rewrote Langston Hughes’s piece HARLEM.

What happens to a dream achieved?

It doesn’t dry up like a raisin in the sun.

It doesn’t fester like a sore and then run.

It don’t stink like rotten meat.

It don’t crust and sugar over like a syrupy sweet.

It don’t sag like a heavy load.

It just explodes!!!

We seem to be turning in the direction of an explosion of blessings built on the victories and sacrifices of the past.

Black Indians - Even Though Denied by Cherokee Family

'I read the news today, oh boy!'

"Cherokee Nation court terminates freedmen citizenship

By Tulsa News - LENZY KREHBIEL-BURTON World Correspondent

Published: 8/23/2011 2:28 AM

Last Modified: 8/23/2011 6:32 AM

TAHLEQUAH - The Cherokee Nation Supreme Court reversed and vacated a district court decision in the freedmen case Monday, immediately terminating the tribal citizenship of about 2,800 non-Indians.

Issued at 5 p.m. Monday, the 4-1 ruling states that because a 2007 referendum that amended the Cherokee constitution to exclude freedmen descendants from tribal citizenship was conducted in compliance with the tribe's laws, the court does not have the authority to overturn its results."

Cherokee Nation does not like Black folks? I don't think so. It's probably about greed over the gambling money and who those in charge have to share with. In the end of the era of greed, I understand, and disagree. They can deny that most African Americans have some Native American blood, but the truth cannot.

Black Indians, like other African Americans, have been treated by the writers of history as invisible. Two parallel institutions joined to create Black Indians: the seizure and mistreatment of Indians and their lands, and the enslavement of Africans. Today just about every African American family tree has an Indian branch. Europeans forcefully entered the African blood stream, but native Americans and Africans merged by choice, invitation and love. The two people discovered that they shared many vital views such as the importance of the family with children and the elderly being treasured. Africans and Native Americans both cherished there own trustworthiness and saw promises and treaties as bonds never to be broken. Religion was a daily part of cultural life, not merely practiced on Sundays. Both Africans and Native Americans found they shared a belief in economic cooperation rather than competition and rivalry. Indians taught Africans techniques in fishing and hunting, and Africans taught Indians techniques in tropical agriculture and working in agricultural labor groups. Further, Africans had a virtual immunity to European diseases such as small pox which wiped out large communities of Native Americans.

The first recorded alliance in earlyAmerica Republic of Palmares in northeastern Brazil Republic of Palmares

The history of the Saramaka people ofSurinam in South America started around 1685, when African and Native American slaves escaped and together formed a maroon society which fought with the Dutch for 80 years, until the Europeans abandoned their wars and sued for peace. Today the Saramakans total 20,000 people of mixed African-Indian ancestry.

By 1650,Mexico Mexico Mexico

Escaped slaves became Spanish Florida's first settlers. They joined refugees from the Creek Nation and called themselves Seminoles, which means runaways. Intermixing became so common that they were soon called Black Seminoles. Africans taught the Indians rice cultivation and how to survive in the tropical terrain ofFlorida U.S. U.S. U.S.

Black Indian societies were so common in every east coast state that by 1812, state legislatures began to remove the tax exemption status of Indian land by claiming that the tribes were no longer Indian. A Moravian missionary visited theNanticoke nation on Maryland

After the Civil War, very few Blacks ever left their Indian nation because this was the only society that could guarantee that they would never be brutalized nor lynched. If Europeans had followed the wonderfully unique model of harmony, honesty, friendship, and loyalty exhibited by the African and Indian populations in North and South America, the "new world" could truly have been the land of the free, the home of the brave, and a place where "all men are created equal."

Albers, J. (1975) Interaction of Color. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Amos, A. & Senter, T. (eds.) 1996) The Black Seminoles. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Bailey, L. (1966) Indian Slave Trade in the Southwest, Los Angeles: Westernlore.

Bemrose, J. (1966) Reminiscences of the Second Seminole War.Gainesville : University Press of Florida

Boxer, F. (1963) Race Relations in the Portuguese Colonial Empire 1415-1825. Oxford: Claredon Press.

Browser, F. (1974) The African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524-1650. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Cohen, D. & Greene, J. (eds.) Neither Slave nor Free.. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Covington, J. (1982) Billy Bowlegs War: The Final Stand of the Seminoles.. Cluluota, FL. Mickler House.

Craven, W. (1971) White, Red, & Black: The 17th Cent. Virginian. Charlottesville: Univ. of Virginia Press.

Forbes, J. (1964) The Indian in America’s Past. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Forbes, J. (1993) Africans and Native Americans. Chicago: University of Illinois.

Katz, Loren (1986) Black Indians. New York Macmillan Publishing Co.

Nash, G. (1970) Red, White, and Black: The People of Early America. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

"Cherokee Nation court terminates freedmen citizenship

By Tulsa News - LENZY KREHBIEL-BURTON World Correspondent

Published: 8/23/2011 2:28 AM

Last Modified: 8/23/2011 6:32 AM

TAHLEQUAH - The Cherokee Nation Supreme Court reversed and vacated a district court decision in the freedmen case Monday, immediately terminating the tribal citizenship of about 2,800 non-Indians.

Issued at 5 p.m. Monday, the 4-1 ruling states that because a 2007 referendum that amended the Cherokee constitution to exclude freedmen descendants from tribal citizenship was conducted in compliance with the tribe's laws, the court does not have the authority to overturn its results."

Cherokee Nation does not like Black folks? I don't think so. It's probably about greed over the gambling money and who those in charge have to share with. In the end of the era of greed, I understand, and disagree. They can deny that most African Americans have some Native American blood, but the truth cannot.

From the dynamic history book by Dr. Leroy Vaughn, MD, MBA, Historian, Humanitarian and Honorary African Chief, BLACK PEOPLE AND THEIR PLACE IN WORLD HISTORY, Chapter After 1492, Sub chapter

BLACK INDIANS

BLACK INDIANS

The first recorded alliance in early

The history of the Saramaka people of

By 1650,

Escaped slaves became Spanish Florida's first settlers. They joined refugees from the Creek Nation and called themselves Seminoles, which means runaways. Intermixing became so common that they were soon called Black Seminoles. Africans taught the Indians rice cultivation and how to survive in the tropical terrain of

Black Indian societies were so common in every east coast state that by 1812, state legislatures began to remove the tax exemption status of Indian land by claiming that the tribes were no longer Indian. A Moravian missionary visited the

After the Civil War, very few Blacks ever left their Indian nation because this was the only society that could guarantee that they would never be brutalized nor lynched. If Europeans had followed the wonderfully unique model of harmony, honesty, friendship, and loyalty exhibited by the African and Indian populations in North and South America, the "new world" could truly have been the land of the free, the home of the brave, and a place where "all men are created equal."

$10 .pdf available on lulu

BLACK INDIANS BIBLIOGRAPHY

Connected to Amazon Associates

Support This Work -

Buy The Books That Inspire You

Buy The Books That Inspire You

Amos, A. & Senter, T. (eds.) 1996) The Black Seminoles. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Bailey, L. (1966) Indian Slave Trade in the Southwest, Los Angeles: Westernlore.

Bemrose, J. (1966) Reminiscences of the Second Seminole War.

Boxer, F. (1963) Race Relations in the Portuguese Colonial Empire 1415-1825. Oxford: Claredon Press.

Browser, F. (1974) The African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524-1650. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Cohen, D. & Greene, J. (eds.) Neither Slave nor Free.. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

Covington, J. (1982) Billy Bowlegs War: The Final Stand of the Seminoles.. Cluluota, FL. Mickler House.

Craven, W. (1971) White, Red, & Black: The 17th Cent. Virginian. Charlottesville: Univ. of Virginia Press.

Forbes, J. (1964) The Indian in America’s Past. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Forbes, J. (1993) Africans and Native Americans. Chicago: University of Illinois.

Katz, Loren (1986) Black Indians. New York Macmillan Publishing Co.

Nash, G. (1970) Red, White, and Black: The People of Early America. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)